BENNY ANDREWS: NO MORE GAMES

CURATED BY ANDREA BRIGHT

At a heightened time of racial tension, Black Americans continued the exploration of decolonized identities. Efforts for equal opportunity and acknowledgement were now some of the main focuses for the Black community, which, in turn, begs the question: “Where does one draw the line?”

Andrews created No More Games winter of 1970 during the peak of his battles against racial discrimination within world-renown museums such as The Whitney Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET), being fully absorbed in the Black arts scene, and working as a teacher for various art programs and schools. Taking on the role of both educator and defender of Black creatives and culture, No More Games represents a major shift in Andrews’ firey mindset during these conflicts.

The large 8.4ft by 8.4ft painting depicts a seated Black male figure gives viewers an empty stare off into the distance mimicking his empty hands and barren landscape. His elongated shadow stretches behind him drawing us to the next panel to the right (of the viewer). A White female figure sprawled on the ground belly up with an American flag draped upon her body where only her limp limbs are exposed. Both of these figures in conversation with and in opposition of one another is symbolic of the longstanding battle between Black Americans and the institution of America itself, a relationship tethered into the identity of Black people in America and the outcast of Black people in American society. Andrews reflects his firsthand experiences with battling racial discrimination and omission of him and his community from art institutions and mainstream art scenes as well as touching on the universal experience of Black Americans being consistently excluded from the conversation. No More Games is an expression of exhaustion most if not all Black people feel when having to constantly be community defenders against the American Institution. The title No More Games reinforces the visual metaphor expressed through imagery. No More Games as a title draws a line in the sand as Andrews himself is exhausted from his frequent conflicts. No More Games as a painting commands the end of wrongdoing or misconduct that plagues many of Andrews’ experiences while living in a racist society and battling racist institutions. After examining Benny Andrews’ archive, I was able to discover more about this period of time in his life and how it significantly affected the way he produced allegory in his pieces.

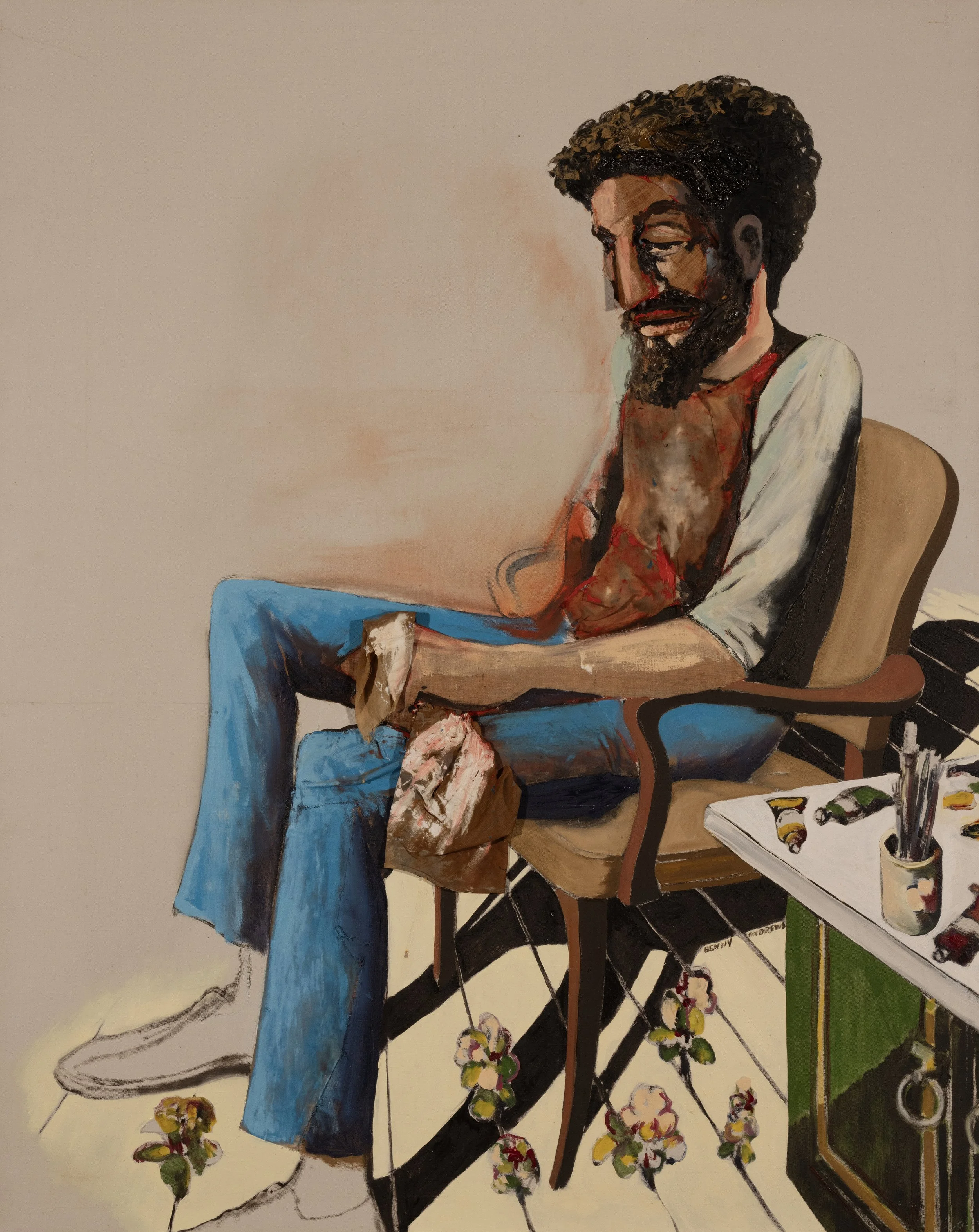

PHOTOGRAPHS of Benny Andrews in his studio working on No More Games - 1970.

Up close and personal, Rudolph “Rudy “Robinson captured a series of photographs of Benny Andrews in the midst of his creative process. Andrews is seated on the floor in close proximity with the canvas, he carefully paints in small sections with intense intention to detail. These photographs are of Andrews creating No More Games in 1970. Andrew’s hands-on approach to confronting the canvas in this manner is both a technique and a philosophy that he carries on in many aspects of his life such as his work with the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC). The unique documents puts us in the moment of the work’s creation and, with a handwritten date, lets us know the work was being made in December of 1970. In the winter of 1970, the BECC protracted struggle with the Whitney – documented Andrews correspondence with the museum leadership– we’re coming ahead. In light of the museum's failure to hire Black curators Andrews and the BECC decided to boycott.

STUDIES IN PEN AND INK

Andrews created “study” drawings and paintings to further develop his visual metaphors and decide what best conveyed messages to viewers. Andrews would employ various techniques, positions, perspectives and alter the composition of a piece until the product was satisfactory. This thorough process of art making would leave a lot of room for Andrews to reuse scrapped elements and expand his range of expression.

The series of drawn studies illustrates Andrews’s process - exploring surreal and symbolic imagery. We see the evolution of the image that eventually becomes No More Games, starting with studies of athletes, a theme that resurfaces often which we can infer a connection to a similar meaning behind one of BA’s most well-known works, Champion. The self portrait Edge of Reality shows Andrews in his natural habitat (the art studio) where he rests in a chair slouched and exhausted. This self portrait reflects the internal and more personal emotions of Andrews at the time of such heightened tension. The athlete figure in Champion sits in anticipation of the upcoming fight, an intentional choice by Andrews by using the boxer as a symbol. This is unlike Andrews in Edge of Reality depicting himself in a more introverted position. Andrews using symbolic elements like athletic figures or even himself is exemplary of his ability to convey visual metaphor powerfully.

THE BLACK EMERGENCY CULTURAL COALITION and CONFLICT WITH THE WHITNEY

The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) was founded by Andrews, along with other notable artists like Henri Ghent and Ed Taylor in reaction to the Metropolitan Museum’s controversial Harlem On My Mind exhibition in 1968. The exhibition analyzed Harlem Black culture while omitting Black people and artists from the exhibition’s works and curatorial process. Andrews and fellow artists protested the event because of its misrepresentation and later formed the BECC as a way to protect and defend the voice of Black artists and curators.

The BECC was very attentive to the interest of Black artwork and culture in institutional conversations, the group had several meetings with museums like the MET and the Whitney to negotiate more diversity in the curatorial staff and the subject matter of future exhibitions.

The BECC and The Whitney Museum of American Art have had a long standing turbulent relationship. Andrews, as a representative of the BECC, recounts his first hand experiences with difficulty negotiating with the Whitney Museum.

The BECC held several protests against the Whitney over the course of the organization’s existence. A notable disagreement between the BECC and the Whitney was the protest against the Whitney’s exhibition Contemporary Black Artists in America in 1971. Members of the BECC negotiated an exhibition to highlight notable Black American contemporary artists under the conditions of having a lack advisory board and Black consulting curators, the Whitney did not adhere to their promise sparking the protest and the Rebuttal Exhibition held at the Acts of Art Gallery. Andrews’ disagreements with the Whitney was one of the many experiences that fueled subjects in his artworks around the time of these conflicts.

CONNECTIONS

1967 - The Champion

The Champion is a pivotal piece for Andrews which has been exhibited numerous times throughout his entire career. Champion directly reflects how Andrews persevered despite limitation and struggle. As described by Andrews in his New York Times article “On Understanding Black Art,”

“I wanted to show the strength of the Black man, the ability to persevere in the face of overwhelming odds, and I used the symbol of the prizefighter. I remember the fights of Joe Louis and how his strength carried us through so damn much and today I think of the strength that Muhammad Ali has shown in his battles for his principles, so when I was working on The Champion I was trying to capture the essence of that thing, whatever it was that the Black man was…”

December 1970 - Edge of Reality with the Whitney

EDGE OF REALITY Andrews uses this self portrait to describe his personal feelings of exhaustion from his community efforts from teaching to being a community leader (co founder of BECC) to being an activist fighting against institutional discrimination within mainstream museums. The self portrait offers viewers a look at the private life of a true crusader, where he sits quietly in stillness, resting from his societal battles.

1971 Trash and The Bicentennial Series

Benny Andrews created Trash as a part of The Bicentennial Series. The Bicentennial series was Andrews’ reaction to the bicentennial anniversary celebrating Declaration of Independence. Andrews anticipated the celebration would not include any mention of Black Americans, or a small section on slavery and disparities which the community was far removed from. Andrews dedicated 5 years to the project with each painting taking one year to create. Through this painting Andrews denounces all American systems that have failed its people and “takes them to the trash.” Three Black figures drag cargo platforms chained together toward a junk yard; on each platform there is a traditionally American value that is visually conveyed by elements symbolizing each theme (religion, liberty, war/law enforcement, etc.). Trash symbolizes Andrews being fed up with the status quo and calling for change by first ridding us of the harmful systems imbedded in the larger American institution.